As a lifelong learner and student of many subjects, one of my greatest regrets is that I didn’t learn and practice good thinking skills early in my life. Many of my life’s lessons (failures) have been unnecessarily painful because of that.

Today I want to share with you a couple of pertinent articles that got me thinking about what I could do to stimulate thinking among my fellow life travellers. The first one is by Seth Godin. The second by Mat Harper.

Tools for modern citizens

It has taken us by surprise, but in our current situation, when everyone has more of a voice and more impact on the public than ever before, it suddenly matters. You wouldn’t take your car to a mechanic who didn’t know how to fix a car, and citizens, each of us, should be held to at least as high a standard of knowledge.

Everyone around us needs to know about:

The mechanics of global weather

Either we are the makers of our future or we’re the victims. And if we don’t understand these fundamental components of how the world works, our actions may undermine our goals and the people around us.

The world is changing fast and we’re all more connected than ever before. The good news is that these are all skills that can be learned, and it’s imperative that we teach them to others.

And here’s some history leading up to how we’ve been fooled and continue to be fooled every day…

Understanding Propaganda: A History of How You Get Fooled Daily

Author:

Matt DB HarperJan 25, 2018

There once was an old German education professor who also happened to be a magician. He would sometimes entertain drifting students with an unexpected magic trick during class, like pulling a coin from a sleepy student’s ear. If a student happened to compliment him on his ability, he’d mumble, “Keine Hexerei, nur Behändigskraft.” Which means: “No magic, just craftsmanship.” The craft he spoke of entails engaging the viewer in a visceral way to create a new reality (a “perceived” reality that is, by no coincidence, in harmony with the intent of the director,) and this “created/fantasy” reality then promotes a stronger emotional bond to the subject by diluting any detachment the viewer may have had previously. Much like the master illusionist, the propagandist works in the same way, swaying and influencing public opinion by means of creating a disassociation between public opinion and personal opinion. In so doing he utilizes the natural confusion that results from humanity’s need to translate their beliefs into reality and creates or manipulates a supposed desire for action. Simply put, propaganda tells you an idea is true, and then reinforces its assertion by fooling you into believing you came to the conclusion independently – or even better, that you had held the belief all along.

Interestingly, not long before the popularization of propaganda, German psychologist Sigmund Freud pioneered the study of human will in correlation with the conscious and unconscious being. He proposed that man did not in fact enjoy the luxury of free will, but rather was a slave to his own unconscious; that is to say all of man’s decisions are governed by hidden mental processes of which we are unaware and over which we have no control. Most of us largely overestimate the amount of psychological freedom we think we have, and it is that factor that makes us vulnerable to propaganda. Drawing directly from the studies of Freud, the psychologist Biddle demonstrated that “an individual subjected to propaganda behaves as though his reactions depended on his own decisions…even when yielding to suggestion, he decides ‘for himself’ and thinks himself free—in fact he is more subjected to propaganda the freer he thinks he is.”

The successful use of propaganda depends on the creator generating some emotional response in the viewer. If the subject is political, for example, then fear (the most popular), moral outrage, patriotism, ethno-centrism, and/or sympathy are typical responses that the propagandist might try to elicit. This is done by attacking the surface consciousness of the masses and creating a disassociation between public opinion and the propagandee’s personal opinion. In doing so, the individual will work out “justifications and decisions for behavior which will conform to social demands in such a way as to make him least aware” of his guilty conscience.

The notion of propaganda is one whose origin could probably be traced back to the dawn of man. If the people of a tribe were in need of food they would come together around the fire, call to the hunter, inform him as to the necessity of food from the next hunt, and the hunter would be forced (by both responsibility and his conscience) to go out the next day and do his best to bring back food for the tribe. Here we can imagine the first sign of man acting regardless of his own desires in the name of societal betterment. Surely he is not the only one capable of finding and delivering food, yet he has accepted this role and does it to the best of his abilities when called upon to do so simply because it is so.

Conversely, the word “Propaganda” is a relatively new term and is most often associated with ideological struggles in the twentieth century. The American Heritage Dictionary delivers a relatively simplistic definition of propaganda as the systematic propagation…of information reflecting the views and interests of those advocating such a doctrine or cause. In other words, assertions given by those who support them.

Political Attack Ads

The first documented use of the word ‘propaganda’ was in 1622, when Pope Gregory XV attempted to increase church membership by strengthening belief (Pratkanis & Aronson, 1992). Whether for the betterment of the congregation or the institution, Pope Gregory XV sought to directly influence theological “belief”. The relevance of this event lies in the fact that the focus of modern propaganda, as we speak of it, is a manipulation of belief. Beliefs, those things known or believed to be true, were realized even in the seventeenth century to be important foundations for both attitudes and behavior and therefore the essential target of modification.

In Europe propaganda was quite impartial during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries describing various political beliefs, religious evangelism and commercial advertising. Across the Atlantic, however, propaganda sparked the creation of a nation with Thomas Jefferson’s writing of the Declaration of Independence. The popularity of literary propaganda had spanned the globe and the medium was made famous in the writings of Luther, Swift, Voltaire, Marx, and many others. For the most part, propaganda’s ultimate goal throughout this time was the increased awareness of what their author’s genuinely believed to be truth. It was not until the First World War that the “truth” focus was reconsidered. Around the world, advances in warfare technology, and the sheer scale of the battles being fought, made traditional methods of recruiting soldiers no longer sufficient. Accordingly, newspapers, posters and the cinema, the various media of mass communication, were used on a daily basis to address the public with calls to action and inspirational anecdotes – with no mention of lost battles, economic costs, or death tolls. As a result, propaganda became associated with censorship and misinformation as it became less of a mode of communication between a country and its people, but a weapon for psychological warfare against the enemy.

The tremendous importance of propaganda was soon realized and the United States organized the Committee on Public Information, an official propaganda agency, whose goal was to raise public support of the war. With the rise of mass media, it soon became apparent to the elite that film would prove to be one of the most important methods of persuasion. The Germans regarded it as the very first and most vital weapon in political management and military achievement (Grierson, CP). By World War II, propaganda was adopted by most countries – except those democratic countries who avoided the negative connotation the term, and instead cleverly distributed information through the guise of “information services” or “public education.” Even in the US today, the methods of providing and the learning of knowledge are deemed “education” if we believe and agree with those propagating the information, and considered “propaganda” if we do not. Not coincidently, central to both education and propaganda are the roles of the fact, the statistic, and that which the target believes to be true.

Propaganda’s modern connotation is that of mass persuasion attempts to domineer established beliefs. However, great thinkers and theorists have been studying persuasion as an art for most of human history. In fact the persuasion of a viewing party has been an important discussion in human history ever since Aristotle outlined his principles of persuasion in Rhetoric. With the birth of modern technology and the development of film, propaganda became a significant and perhaps the most highly effective form of persuasion through the utilization of one-way media. As early as 1920, a scientist named Lippman proposed that the media would control public opinion by focusing attention on selected issues while ignoring others. And it is no secret that the vast majority of people obediently think as they are told. It’s just human nature–who has the time or the energy to sort out all the issues one’s self? The media does this for us. Censorship and one way media protect the few from extraneous or divertive impulses that might lead him to examine the new reality in a way that doesn’t harmonize with the director’s intent. It offers us safe, often comforting opinions that appear to be the consensus of the nation. It appeals to the masses “through the manipulation of symbols and of our most basic human emotions” to achieve its goal – that of the viewer’s compliance.

Compliance is an easy and immediate solution to a social problem. Compliance does not require the target to agree with the campaign, just simply perform the behavior. Such an accomplishment was not easily attained, and it took some of the greatest, and most vicious, minds of our time to do so effectively.

Propaganda adheres wholeheartedly to the moral that the supreme good is the confusion and defeat of the enemy. The propagandist must have a full understanding the words and images that portray his message and a method to deliver the combination in a way to implant the message with out divulging that it is doing so. John Grierson argues that free men are relatively slow on the uptake in the first days of crisis…(and) your individual trained in a liberal regime demands automatically to be persuaded to his sacrifice…he demands as of right—of human right—that he come in only of his own free will. Great propagandists are successful because they have a great understanding of how to reach the heart of the masses. To borrow an example from Dr. Kelton Rhoads, they went beyond simplistic thinking like, “What can we say to make people decide to buy a car?” but rather, “What makes people decide to say yes to all sorts of requests–to buy a car, to contribute to a cause, to take a new job?”

One person who had full knowledge and took full advantage of man’s inherent vulnerability was Adolf Hitler. Considered the greatest master of scientific propaganda in our time by John Grierson, Hitler said outright, ‘…the infantry in trench warfare will in future be taken by propaganda…mental confusion, contradiction of feeling, indecisiveness, panic; these are our weapons.’ Sun Tzu said, to subdue the enemy without fighting is the highest skill. Hitler had such a skill, and by utilizing his “weapons” Hitler was able to predict and cause the fall of France in 1934, as well as strike fear in the eyes of outside nations while rousing the hearts and courage of a rising army within.

Propaganda relies heavily on different tactics of persuasion to manufacture a specific belief in the mind of the viewer. Depending on who you ask there ranges anywhere from two to over ninety tactics that exist on many levels and degrees of intensity. To be effective, propaganda has to make a complex idea simple as its success is based on the manipulation and repetition of these ideas. In looking directly at Hitler’s use of propaganda film we will put our focus towards its reliance on confusion of fantasy and reality through the style of realism and extratextual conditions.

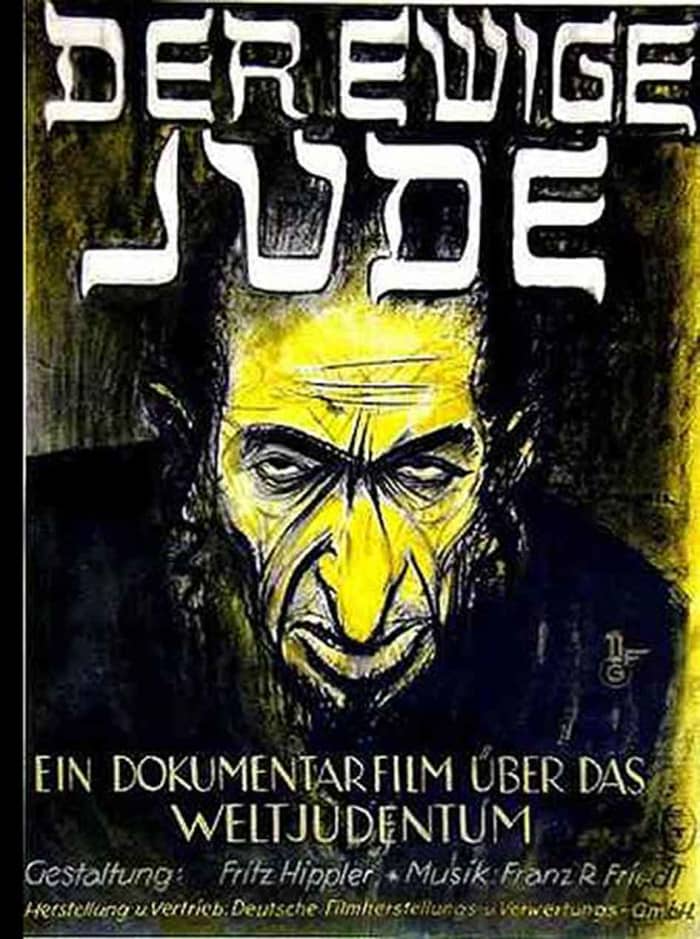

The most notorious of the Nazi “fantasy/reality” films is called “The Eternal Jew.” Under the insistence of Joseph Goebbles, this film was assigned to and produced by Fritz Hippler as an anti-Semitic “documentary”. Characteristic of Hippler, this film, often called the “all-time hate film”, relied heavily on narration in which anti-Semitic rants coupled with a selective showing of images including pornography, swarms of rodents, and slaughterhouse scenes that alleged to display Jewish rituals. His footage showed masses of the hundreds of thousands of Jews that were herded into the ghetto, starving, unshaven, bartering their last possessions for a scrap of food and described the horrific scene as Jews “in their natural state.” He showed rats scurrying in droves from the sewers and leaping at the camera while the narrator comments on the spreading of the Jews “like a disease” throughout Europe: “Wherever rats turn up, they spread annihilation throughout the land… Just like the Jews among mankind, rats represent the very essence of malicious and subterranean destruction.” Hippler dutifully provides before and after photos of Jews attempting to hide their true selves behind a façade of civilization allowing German audiences to recognize them for who they truly are and not be fooled by there cheating, filthy, parasitic species. The audience is then provided a supposed history on the Jew and his deceptive ways. This is done so by showing “documented” scenes from the fiction film The House of Rothschild. We see a rich Rothschild, played by George Arliss, hiding food and changing into ratty old clothing to deceive and cheat the tax collector, and are expected to accept it as fact rather than a Hollywood production. The film goes so far as to single out Albert Einstein (at this time already quite famous) by showing his picture with the commentary: “The relativity-Jew Einstein, who concealed his hatred of Germany behind an obscure pseudo-science.” Though seeming absurd today, the film acted then to incite an anxiety and confusion in the German people at the threat of a thriving disease-ridden people, and seemingly no solution for the problem. The climax of the film is a powerfully disturbing warning and declaration of hate by Hitler himself assuring the people that there is no problem. Taken from a speech to the Reichstag in 1939 it translates as:

If the international finance-Jewry inside and outside Europe should succeed in plunging the nations into a world war yet again, then the outcome will not be the victory of Jewry, but rather the annihilation of the Jewish race in Europe!

Closure comes in the foreboding words of Hitler as he adamantly proclaims that all of these troubles will soon be taken care of.

Although this passing off of fiction footage as documented truth is today simply embarrassing and completely counter-effective, it was not an entirely new concept at the time. In reality, the method of sampling footage from other films to enhance your own was becoming quite common. In America, for instance, it was feared by officials that anti-war and anti-foreign entanglement feelings prevailed between the wars, and in general the ordinary American didn’t give “a tinker’s dam” about Hitler (Rowen, 2002). The Army had actually been producing hundreds of training films but Chief of Staff George C. Marshall was looking for something different. He mapped out objectives and hired Hollywood director Frank Capra to carry out his proposed Why We Fight film series, essentially to justify fighting in such a long and costly war. But along with the arduous task of completing Marshall’s 6 objective plan, Capra undertook perhaps the one most basic and fundamental objective that a film used in troop information sessions had: holding the audience’s attention. As such, it was necessary to have footage that was not only exciting but displayed a positive outlook on the war for “our boys,” no matter the source. This is a major reason why “The Nazis Strike” and the Why We Fight series in general are probably best described as compilation films rather than documentary and therefore very much a job of effective editing. Set on the objective of boosting moral, Capra hired Hollywood actor Walter Huston as a narrator, commissioned Disney to produce maps and animation through an agreement with the government, and cut between footage from US Federal programs and, a propaganda masterpiece, Leni Reifenstahl’s Triumph of the Will to keep a fast paced and interesting series of films.

Upon its release in 1935, Leni Reifenstahl’s Triumph of the Will, a documentary of the sixth Nazi Party Congress at Nuremberg, displayed beyond doubt the power of propaganda film. Hitler’s descent from the sky in a shiny silver airplane presents him as a deity on the helm of technological achievement. Always looking down upon the people he so cares for, his demeanor is always pleasant. In fact the only time he gets riled up is for a speech, and then we get see just how energetic and passionate he can be when it comes to achieving the best for his country and its people. Through an extraordinary choreography of images and sounds, from marching men, swastikas, cheering women and children, and folksongs, the film inspired some, terrified others, and ultimately rallied many to the Hitler cause. No film was more widely used by opposing forces to vividly display the wicked nature of its enemy than Triumph of the Will. Striking a blow against the opposition by provoking fear while at the same time calling to arms the loyalty of thousands upon thousands, this tremendous outpour of emotion and action as a result of masterful imagery and film editing is the epitome of what propaganda stands for.

German audiences reacted to The Eternal Jew with cheers at the suggestion of the annihilation of the Jewish race in the film. Reminiscent of Cicero and his renowned ability in ancient Rome to demonstrate murdering villains as laudable patriots and have them subsequently acquitted, Hipple presents Hitler, (apparently) convincingly to Germans, as a hero rather than a eradicator for his plans to extinguish an entire race of people. Reifenstahl edits in the sounds of roaring crowds at the conclusion of the descent of Hitler in his flying machine from the heavens above. In Triumph of the Will, the Fuhrer was a gentle simple soul, serving his people, humble in his triumphs. Capra, in turn, used the tools of Hollywood to glamorize and rally up our troops in support of a war that was killing thousands and costing millions. What we come to realize is that very little importance is given to whether or not propaganda is true, but rather it is whether or not it gets someone to act. In these cases they did exactly that.

Conversely, with the rising popularity of injecting the masses with beliefs, there came another movement in direct opposition: film which sought to control the sub-consciousness of a people. Leading the way was surrealist Luis Bunuel with his stunning satireLand Without Bread. Bunuel took a village of average people from the mountains of Spain and created a sad, decrepit world full of misery and death simply to mess with your head. The statement he was making was in fact quite bold and executed so well that it made you seriously question your susceptibility to deception. His portrayal of tragic scenes of an unlucky goat, and, you are told, starving children who have to stay at school to eat their bread for fear of it being stolen by their greedy parents, accompanied by a soundtrack of heroic and upbeat music works effectively to pry apart your acceptance of what is real and question what it is you are watching.

In a complete opposite method, John Huston’s Battle of San Pietro seeks to dispel our skepticism in the legitimacy of film by divulging as much information in the most descriptive details possible as to leave no question of its sincerity. This abundance of information acts to put you in the place of a real soldier as you follow, side by side with the infantry, watching the action, even experiencing the death of fellow soldiers as we see the life extinguished of two people, both from in front and behind the camera. Its chilling realism sought to let you have the whole experience on your own rather than edit out the bad parts.

Alain Resnais’ Night and Fog served two purposes. That of a vigorous indictment, and that of a lesson for those to come. He frequently shifts back and forth from warm colored, serene images of the former extermination camps to horrific black and white images of the carnage they produced. In a time when documentarists were in no way being subtle about the films they made, Resnais used his film to take a calm and composed look back at the horrific incidences that took place and at the death camps and establish a need, not for acceptance, but for remembrance. He used film in a shockingly beautiful and gruesome way to express the importance of not forgetting those that were lost.

There is an insidious psychological process called the “Self-serving Bias.” This bias leads us to believe that we are immune to the influences that affect the rest of humanity. And it is that belief that these three film makers were directly aiming at exploiting. They rely more on an empathetic identification than anything else. By eliciting a strong emotional response from the viewer, the viewer is persuaded to believe his feelings take precedence over an authoritative or legislated principle or rule. For example, modern Christianity tends to see the Ten Commandments as mood oriented suggestions rather than moral absolutes. If our feelings are strong enough, then God will grant dispensation. “It just seemed to be so right for me”…..denies authority to “thou shalt not commit adultery” for example.

Dr. Kelton Rhoades delivers the example to television watchers old enough to remember the Kung Fu television program. “Whose side were you on when the prejudiced, muscle-bound drunk lunged at peace-loving David Carradine with a broken beer bottle? Did you enjoy watching Carradine turn the enraged belligerent’s charge into a devastating floor-slam? The point is that these films invoke a sense of emotion that suddenly makes us realize a truth only when we look within ourselves and acknowledge that the so-called “greater good” is not always the greatest good; and often it’s not good at all.

The word “propaganda” is often invoked when it is obvious that objectivity in a film has ceased. The irony is that the term is invoked precisely when the film has failed as propaganda. When the choices please us, we do not mention it. In a sense, all film makers are propagandists as they try to create a mood for the viewer and invoke feelings to draw you into the story. Yet in all fiction, the viewer must maintain a willingness of disbelief. It is not a healthy mind that can watch the Terminator films and not realize that what they are seeing is fiction, no matter how realistic it looks and sounds. “Documentary” and “propaganda” on the other hand, and this is why they can be such manipulative tools, use supposed images of reality to create a story and therefore is seen by the viewer as not requiring that willingness of disbelief. You don’t have to constantly remind yourself that it isn’t real, because it is in fact, in one way or another, “real”, and that is enough to make you believe. As long as you think yourself insusceptible, there will be someone just above you pulling on a string; there will be someone there to pull a coin from behind your ear when you are not doing what you are supposed to.

Bibiliography

Barnouw, Erik (1993) Documentary : a history of the non-fiction film. Oxford: New York

Delwiche, Aaron (1995) Wartime Propaganda: World War I: The Drift Towards War http://carmen.artsci.washington.edu/propaganda/war1.htm

Ellal, Jaques. The Psichic Dissassociation Effect of Propaganda . CP pg. 31-33

Grierson, John . The Nature of Propaganda . CP , pg. 13-19

Hornshoj-Moller, Stig. (1998) On ‘The Eternal Jew’ http://www.holocaust-history.org/der-ewige-jude/

Hornshøj-Møller, Stig, (1997) Paper presented at the conference “Genocide and the Modern World,” Montreal, Canada

Pratkanis, A. & Aronson, E. (1992). Age of Propaganda. Freedman: New York.

Rhoads, Kelton Ph.D. “Introduction to Influence” www.workingpsychology.com , 1997/2002

Wistrich, Robert S. (1996) Weekend in Munich: Art, Propaganda and Terror in the Third

Reich. Trafalgar Square

© 2017 Matt DB Harper

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.